Neutrino Catcher

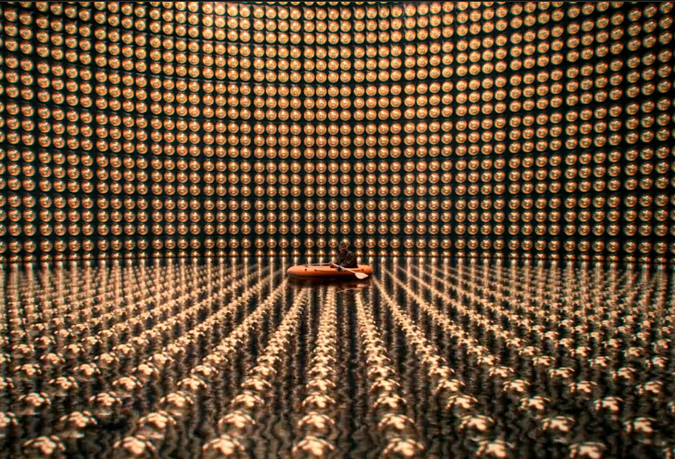

Super-Kamiokande Neutrino Catcher developed by the ICRR

Curation + Essay by Robert Kirkbride

Assisted by Lorenz Wittenberg

Featuring the photography of Lisa Marie Blohm, Katie Carlisle, Yvonne Laube, Robert Lewis, Rachael Pollack,

Ray Staten, Rusty Tagliareni + Christina Mathews, Jamie Tirado, Vincent Verna, and Robert Kirkbride

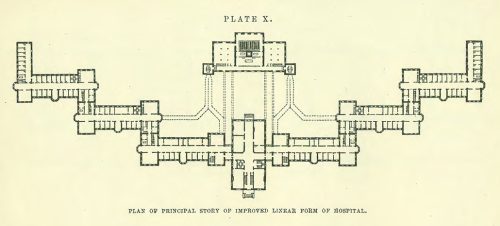

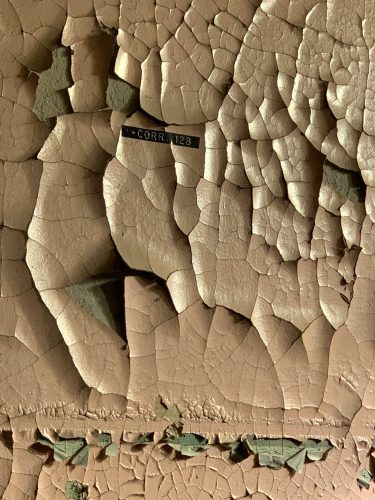

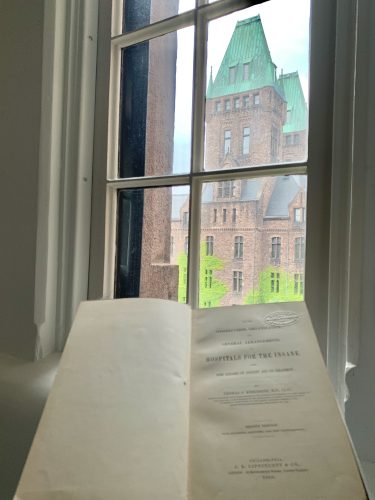

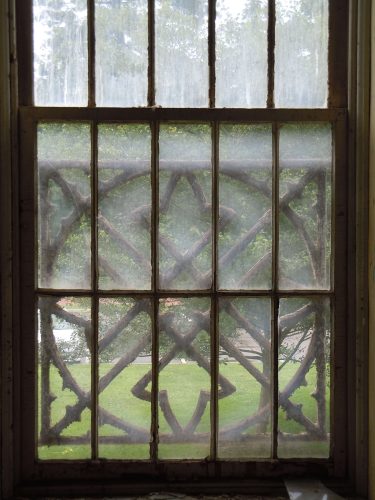

Figure 1. Photographic collage of Thomas Story Kirkbride’s “Improved Linear Plan” for an idealized hospital for the mentally ill, from the second edition of his influential treatise (1880). Sixty images of thirteen Kirkbride Plan hospitals are featured in the photography of eleven PreservationWorks members, including Lisa Marie Blohm, Katie Carlisle, Yvonne Laube, Robert Lewis, Rachael Pollack, Ray Staten, Rusty Tagliareni + Christina Mathews, Jaime Tirado, and Vincent Verna, and Robert Kirkbride. The visual documentation of decay in these hospitals supports efforts to record, preserve, and adaptively reuse remaining structures. Four of the “Kirkbride Plan” hospitals represented have since been demolished, six have been preserved and repurposed, and three are currently at risk.

Figure 1. Photographic collage of Thomas Story Kirkbride’s “Improved Linear Plan” for an idealized hospital for the mentally ill, from the second edition of his influential treatise (1880). Sixty images of thirteen Kirkbride Plan hospitals are featured in the photography of eleven PreservationWorks members, including Lisa Marie Blohm, Katie Carlisle, Yvonne Laube, Robert Lewis, Rachael Pollack, Ray Staten, Rusty Tagliareni + Christina Mathews, Jaime Tirado, and Vincent Verna, and Robert Kirkbride. The visual documentation of decay in these hospitals supports efforts to record, preserve, and adaptively reuse remaining structures. Four of the “Kirkbride Plan” hospitals represented have since been demolished, six have been preserved and repurposed, and three are currently at risk.

Ancient Egyptians believed that the seat of the soul was in the tongue: the tongue was a rudder or steering-oar with which a man steered his course through the world.

Bruce Chatwin (1988, 271)

Taste and Wisdom

This brief meditation on taste and wisdom in the nineteenth century Kirkbride Plan hospitals is the fourth in a series of research projects in which the senses offer literal and metaphoric tools to better understand these remarkable and complex places. [For links to the other projects, see below] The ancient relationship between taste and wisdom is seated in the gustatory experience of flavor – sapor – and the physiological and aesthetic responses that interplay between our tongues and our minds. As we experience a taste, we inevitably compare it with other tastes previously encountered and encoded in our memories. The word savory, an adjective describing complex flavor profiles while also connoting wholesomeness and acceptability, stems from sapor. So, too, does the verb savor, the act of taking pleasure in a flavor or other memorable experiences, such as “savoring victory.”

Distinguishing one’s personal preferences, or tastes, from those shared with one’s family, friends, and the world at large, is cumulative and identity-forming. Sapor is also the etymological root of sapience, the wisdom of good taste and judgment formed from our discernment and distillation of the “flavors” acquired in our worldly experiences (Frascari 1986, 4). And yet, tastes are never exclusively one’s own. Our patterns of choice-making, our inclinations and predilections, are as deeply encoded from our ancestors and contemporaries as they are uniquely our own. We are each multi-fibered textiles spun from personal and pre-personal experiences, revealing that we are always and yet never quite our “selves.”

What, then, would be tasteful language for a place dedicated to those who may be out of balance with their selves?

Kirkbride Plan Hospitals

[In hospitals for the mentally ill…] all extravagance in the way of ornamentation should be avoided; but such an amount of it as is required by good taste, and is likely to be really beneficial to the patients, is admissible. It does not comport with the dignity of any State to put up its public buildings in a style of architecture which will not prevent their being distinguished from factories or workshops. Especially is this the case with those designed for the treatment of a disease like insanity, in which the surroundings of patients greatly influence their conditions and feelings.

Thomas Story Kirkbride (1880, 46)

In 1854, Dr. Thomas Story Kirkbride published On the Construction, Organization, and General Arrangement of Hospitals for the Insane, a widely influential treatise on the ideal design and management of hospitals to treat mental illness and restore patients to return to the world. The unique architectural arrangement of Kirkbride’s “Linear Plan” (which over time simply became known as “The Kirkbride Plan”), consisted of symmetrical wings that step back from a central administration building in a “batwing” formation, situated in picturesque, landscaped settings. With this configuration, tall, operable windows admitted plentiful sunlight and prevailing breezes for natural ventilation of the interiors, while providing ample views out to the bucolic grounds.

Over all, the terms “taste,” “tasteful,” and “tastefully” appear eight times in the first edition of 1854. In the treatise’s second edition, in 1880, the occurrence of “taste” and its variants nearly doubles, appearing fourteen times. What was the source of this increase in sapor and sapience?

The spread of Kirkbride’s Linear Plan converged with the widening significance of tasteful architecture and landscape design in the popular imagination of a “Young America,” a phenomenon due in large part to the writings and designs of Andrew Jackson Downing, the “apostle of taste.” In the 1840’s and early 1850’s, A. J. Downing became “the preeminent authority on domestic architecture and landscape gardening,” representing for the citizens of a young and rapidly evolving nation that “improvements in taste signified the ‘advancement of civilization’” (Schuyler 2015, 3-4). In 1842, Downing accepted a request for the “benefits of [his] taste and skill” from the managers of a new State asylum in Utica, New York, to design the grounds of the new facility. In March 1848, Downing writes: “Many a fine intellect, overtasked and wrecked in the too ardent pursuit of power or wealth, is fondly courted back to reason, and more quiet joys, by the dusky, cool walks of the asylum, where peace and beauty do not refuse to dwell” (Schuyler 2015, 78-80). That same year, the first Kirkbride Plan hospital opened in Trenton, New Jersey, whose grounds were to be laid out “according to a tasteful design,” by Downing.

If not for his tragic death at the age of 36, in 1852, it is quite likely that A. J. Downing would have received many more commissions for Kirkbride Plan hospitals, around eighty of which were built across North America and Australia. Calvert Vaux, Downing’s partner at the time of his death, and Frederick Law Olmsted, the inheritor of Downing’s mantle in landscape design, were later commissioned to design the grounds for two Kirkbride hospitals that are now National Historic Landmarks, at Buffalo (1872) and Poughkeepsie, New York (1868). Downing’s personal endorsement of the Gothic and Italianate styles shaped the architectural language of numerous Kirkbride Plan hospitals, and his advocacy for tasteful architecture and landscape design clearly influenced Dr. Kirkbride, who writes: “Every hospital for the insane should possess at least one hundred acres of land, to enable it to have the proper amount for farming and gardening purposes, to give the desired degree of privacy and to secure adequate and appropriate means of exercise, labor and occupation to the patients, for all these are now recognized as among the most valuable means of treatment.” Of those hundred acres, “from thirty to fifty acres immediately around the buildings, should be appropriated as pleasure grounds, [of which] it is desirable that several acres of this tract should be in groves or woodland, to furnish shade in Summer, and its general character should be such as will admit of tasteful and agreeable improvements” (T.S. Kirkbride 1854, 7).

Material Histories

Although we now have broader options to diagnose and treat mental illness than those available to Dr. Kirkbride and his colleagues, in a world facing intensifying disasters, pandemics, social and political unrest and injustices, there is still urgent need for places to go. As former head of NIMH, Thomas Insel, argues: “We need places like crisis-stabilization units, opportunities for people to spend maybe 23 hours, maybe seven days, to be able to recover from whatever the acute crisis is” (R. Kirkbride 2024). While there may be reasons not to restore an abandoned Kirkbride solely to its former use as mental health facility, it is worth noting that for conditions such as Post Traumatic Stress, patients benefit from recuperative places much like those conceived by Kirkbride, Downing and Olmsted, with their spacious, light-filled rooms and soothing, natural surroundings. At abandoned sites such as Fergus Falls, MN, whose Kirkbride was briefly a candidate to become a regional PTS treatment center several years ago, such an approach may be extremely pragmatic as part of a mixed-use redevelopment strategy. As successfully demonstrated at Kirkbrides elsewhere, including Traverse City, MI, and Athens, OH, such a blended strategy calls for the sapient good taste and judgment to redevelop with patience, in small bites rather than one big gulp, which, despite its (assumed) convenience, more often leads to indigestion than results worth savoring.

As historical documents, the remaining Kirkbride Plan hospitals embody invaluable lessons for current efforts to improve our mental healthcare. Coupled with the ecological imperative to adaptively reuse – and not squander – our existing infrastructures, it is critical to preserve and repurpose the hospitals. These two principles, combined with the urgency to broaden conversations about places with difficult memories, drive my efforts with PreservationWorks.

PreservationWorks

I am the Spokesperson and a founding trustee of PreservationWorks.org, a non-profit organisation committed to the preservation and adaptive reuse of the 35 remaining Kirkbride Plan hospitals across North America and Australia. We formed in 2015, absorbing the 501c3 charter of the advocacy group, Preserve Greystone, in the wake of the highly contested and unnecessary demolition of Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital, in Morris Plains, NJ, which was ranked as one of the top five architectural losses in the United States that year by the National Trust of Historic Places. Our mission is to share knowledge and resources to support local efforts to reactivate and memorialize these structures and those who lived and worked in them through comprehensive photographic tours, events, and interactive research media on our website, such as the Kirkbride Navigator. Our impassioned network includes urban explorers and other non-traditional preservationists who embrace the challenging histories of Kirkbride Plan hospitals, mindful of their multifaceted value.

Links to sight-, scent-, and sound-based projects about the Kirkbride Plan hospitals

“Phantoms of the Kirkbride Hospitals” (Places Journal 2024), centers on Dr. Thomas Story Kirkbride’s vision for the patient-centered treatment of mental illness, shaped by respectful care and uniquely situated and configured hospitals. It reflects on the visual nature of Dr. Kirkbride’s therapies, which included innovative uses of photography and magic lantern shows, and soothing views to generously landscaped grounds; and it also considers the “optics” of their domestic décor, which, despite beneficent intent, often masked inherent tensions with institutional realities. The second project, “Scent Surveys, Decay and Transformation in the Kirkbride Plan Hospitals of North America,” a chapter in a new book on experimental archaeology (UCL July 2025), investigates the multisensorial continuum between personal experience and cultural memory through the scent of decay. “Scent Surveys” considers the poignant olfactory encounters of ten explorer-preservationists with abandoned Kirkbride Plan hospitals, alongside the miasma theory that informed their characteristic layouts and innovative architectural and technological features. The third project, Sound the Asylum is an ongoing experimental documentation project by composer-producers Melissa Grey and David Morneau, using ambisonic spatial recordings of resonant frequencies to catalog the acoustical properties of rooms once inhabited by patients, caregivers, and visitors at several abandoned Kirkbride Plan hospitals.

Bibliography

Chatwin, Bruce. 1988. The Songlines. New York: Penguin Group.

Frascari, Marco. 1987. “’Semiotica ab Edendo,’ Taste in Architecture.” Journal of Architectural Education, Vol. 40, No. 1. 2-7.

Grey, Melissa and Morneau, David. 2023. Sound the Asylum. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://flowercat.org/sta/

Kirkbride, Robert. 2025, July 1. “Scent Surveys, Decay and Transformation in the Kirkbride Plan Hospitals of North America.” Chapter 8 in New Sensory Approaches to the Past: Applied Methods in Sensory Heritage and Archaeology. Eds. P. Jordan and S. Mura. London, England: UCL Press.

Kirkbride, Robert. 2024, December 10. “Phantoms of the Kirkbride Hospitals.” Places Journal. Eds. N. Levinson, F. Richard, J. Wallaert. Accessed January 9, 2024. https://doi.org/10.22269/241200

Kirkbride, Robert. 2019. “Mnemonics and Pneumatics,” I Stand in My Place With My Own Day Here: Site-Specific Art at The New School. Ed. Frances Richard. New York: The New School. Commissioned monograph on Rita McBride’s Bells and Whistles, a site-specific work at The New School’s University Center, pp. 191-94.

Kirkbride, Thomas Story. 1854. On the Construction, Organization, and General Arrangements of Hospitals for the Insane (first edition). Philadelphia, PA: Lindsay & Blakiston.

Kirkbride, Thomas Story. 1880. On the Construction, Organization, and General Arrangements of Hospitals for the Insane (second edition). Philadelphia, PA: J. B. Lippincott & Co.

Petrarch, Francesco. 2005. Letters on Familiar Matters, Vol. 3. Translated by Aldo Bernardo.New York: ItalicaPress.

Schuyler, David. 2015. Apostle of Taste: Andrew Jackson Downing 1815-1852. Amherst, MA: Library of American Landscape History.

Image Credits

Row 1

Figures 2 – 8, left to right: Robert Kirkbride (Columbus, OH); Jaime Tirado (Buffalo, NY); Robert Lewis (Taunton, MA); R. Kirkbride (Fergus Falls, MN); Vincent Verna (Athens, OH); R. Kirkbride (Weston, WV); R. Kirkbride (Buffalo, NY)

Row 2

Figures 9 – 12, left to right: R. Kirkbride (Buffalo, NY); Ray Staten (Fergus Falls, MN); Rachael Pollack (Weston, WV); Thomas Story Kirkbride/Samuel Sloan (“Improved Linear Plan,” 1880)

Row 3

Figures 13 – 20, left to right: R. Kirkbride (Buffalo, NY); R. Kirkbride (Buffalo, NY); R. Kirkbride (Buffalo, NY); Lisa Marie Blohm (Buffalo, NY); Rusty Tagliareni & Christina Mathews (Weston, WV); R. Kirkbride (Athens, OH); R. Kirkbride (Fergus Falls, MN); Rusty Tagliareni & Christina Mathews (Buffalo, NY)

Row 4

Figures 21 – 26, left to right: R. Kirkbride (Weston, WV); Vincent Verna (Weston, WV); R. Kirkbride (Fergus Falls, MN); R. Kirkbride (Buffalo, NY); R. Kirkbride (Athens, OH); R. Kirkbride (Weston, WV)

Row 5

Figures 27 – 33, left to right: R. Kirkbride (Dayton, OH); Lisa Marie Blohm (Hudson, NY); Rusty Tagliareni & Christina Mathews (Morris Plains, NJ); Ray Staten (Fergus Falls, MN); Ray Staten (Fergus Falls, MN); Jaime Tirado (Weston, WV); Rusty Tagliareni (Buffalo, NY)

Row 6

Figures 34 – 40, left to right: Ray Staten (Fergus Falls, MN); Y. Laube (Hudson, NY); Vincent Verna (Fergus Falls, MN); R. Kirkbride (Salem, OR); Katie Carlisle (Buffalo, NY); Robert Lewis (Taunton, MA); Ray Staten (Taunton, MA)

Row 7

Figures 41 – 46, left to right: Rachael Pollack (Weston, WV); AP Photos, Mel Evans (Morris Plains, NJ); Rusty Tagliareni & Christina Mathews (Morris Plains, NJ); R. Kirkbride (Salem, OR); R. Kirkbride (Fergus Falls, MN); R. Kirkbride (Buffalo, NY)

Row 8

Figures 47 – 55, left to right: Lisa Marie Blohm (Athens, OH); R. Kirkbride (Fergus Falls, MN); R. Kirkbride (Buffalo, NY); R. Kirkbride (Traverse City, MI); R. Kirkbride (Buffalo, NY); Rachael Pollack (Hudson, NY); Vincent Verna (Fergus Falls, MN); Rusty Tagliareni & Christina Mathews (Hudson, NY); R. Kirkbride (Athens, OH)

Row 9

Figures 56 – 61, left to right: R. Kirkbride (Fergus Falls, MN); Ray Staten (Hudson, NY); Ray Staten (Kankakee, IL); Ray Staten (Worcester, MA); Vincent Verna (Fergus Falls, MN); Vincent Verna (Athens, OH)