Contemporary Queer Interiors of NYC

Contemporary queer space in New York consists of a great mix of public and private environments owing a debt of gratitude to the activism of past generations. Queer interiors exist in all parts of New York City, frequently occupying the mainstream venues once culturally off-limits or even illegal. However, the “gay bar” remains one of the most important spaces for queer people. The very presence of these establishments can resist mainstream cis-heteropatriarchy, providing a safe haven for the queer community. From Stonewall Stonewall and Julius to Julius to Henrietta Hudson Henrietta Hudson, gay bars in New York City have played an integral role in advancing LGBTQ+ rights worldwide. And yet, they are often victims of their success. Since the turn of the 21st century, trends have pointed to the closing of gay bars in major US cities (Mattson, 2019). These trends can be attributed to many factors, including increased acceptance of LGBTQ people in Western society, the gentrification of predominantly gay neighborhoods, and the rising cost of rent in large cities (“Lights Out; Gay Bars”, 2016 ).

Additionally, interconnected digital and virtual technology is also disrupting the queer interior. For example, apps like Grindr allow queer people to meet one another without needing a discreet and safe physical place. More recently, these forces, and the COVID-19 pandemic, have led to a downturn in the number of bars – an essential category of queer interior space (Mattson, 2021).

Conversely, the importance of the internet and social media, in particular, as an emerging form of virtual queer space cannot be overlooked. Virtual queer space, facilitated by social media and location-based apps, provides spaces where queer individuals can find community and make connections. These virtual spaces have not only been a lifeline to queer people in communities with less tolerance, but they had proven crucial when pandemic-related lock-downs mandated the separation of bodies in shared physical spaces in 2020. As a result, the queer community adapted and appropriated space on social networking platforms and communication technologies such as Zoom, TikTok, and House Party. The result was a hybrid queering of the digital and domestic spaces in which people interacted and inhabited.

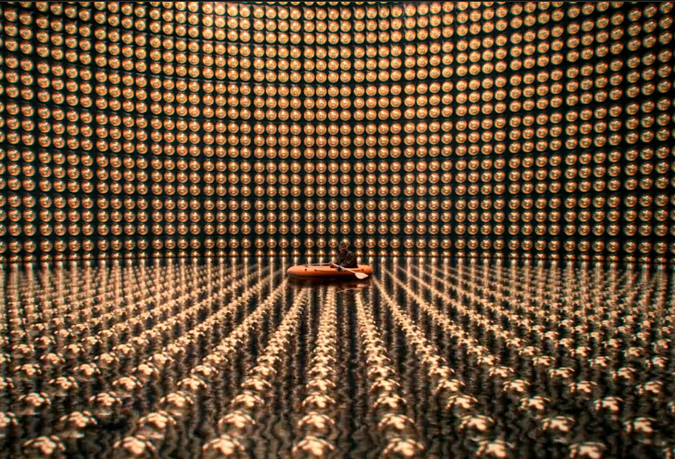

Virtual space continues to grow and hold a place within queer life; however, the experience of physical space is still a significant part of the queer experience. And, contemporary queer interiors in New York City can take many forms beyond the bar. Understanding queer interiors as sites of community and resistance and acknowledging their value for queer people is critical for their survival. In this curated entry, we have organized queer interiors into three groups: sites of community, pleasure, and care (see Figure 1). Within the community category are spaces where the exchanges of shared knowledge, culture, experience, goods, and history among queer people support the development of queer identity. Locations that elicit pleasure connect individuals through opportunities for uninhibited embodiment. Lastly, places of care provide comfort and support to a community that might not have received this support elsewhere. However, queer interiors are amorphous, and they exist beyond and between any artificial boundary; instead, they often hold several of the aforementioned three characteristics at varying times.

(Figure 1: Diagram of category of contemporary queer space)

Lights out; gay bars. (2016, Dec 24). The Economist, 421, 99. Retrieved from https://login.libproxy.newschool.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/magazines/lights-out-gay-bars/docview/1862124736/se-2?accountid=12261

Mattson, G. (2019). Are Gay Bars Closing? Using Business Listings to Infer Rates of Gay Bar Closure in the United States, 1977–2019. Socius. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023119894832

Mattson, G. (2021, April 5). Shuttered by the coronavirus, many gay bars – already struggling – are now on Life support. The Conversation. Retrieved February 6, 2022, from https://theconversation.com/shuttered-by-the-coronavirus-many-gay-bars-already-struggling-are-now-on-life-support-135167

Queer Spaces of Community

George Chauncey once said that “there is no queer space, there are only spaces put to queer uses” (Chauncey, 1996, p. 224). The actors needed to manifest queer interiors are queer people themselves. Therefore, a central tenet of queer space is the notion that you can surround yourself with like-minded individuals. Not all queer individuals are afforded the privilege of security, acceptance, or comfort in normative spaces. Only through specific environments are queer people able to express and develop themselves without fear of rejection or repercussions. With this in mind, queer spaces that foster community are locations where individuals share knowledge, experiences, culture, crafts, goods, and services.

Interiors that enable community building are constructed with flexible programs. Different communities may require vastly different things. As such, queer community spaces may be flexible, designed with a range of uses in mind. Museums, galleries, and clubs achieve flexibility through the open space. The open floor plan allows for a constant reworking of the program to enable many options. Within a similar vein, retail stores and chat rooms allow for flexibility through the constantly shifting nature of the objects that compose the space. Both the books and the chat windows are in a constant state of flux. The shifting nature of the elements that make up these interiors allows for a variety of possible interactions.

Chauncey, G. (1996). Privacy Could Only Be Had in Public: Gay Uses of the Street. In Stud: Architectures of Masculinity (p. 224). essay, York: Princeton Architectural Press.

Queer Spaces of Pleasure

Joy and pleasure can occur anywhere. But, for queer people, choosing joy and achieving pleasure requires safety that is not always available in dominant cis-heteronormative culture. Merriam-Webster defines joy as “a feeling of great happiness” (Merriam-Webster, n.d.) that exists within our consciousness. In our context, pleasure is better considered in its verb form, “to pleasure,” where the feeling of gratification and joy is given to the recipient by others. Neither of these experiences can manifest without queer interiors that allow for unrestrained self-expression. The comfort and safety offered by queer space enable individuals to experience a freedom that is impossible in heteronormative spaces. Adrienne Maree underscores the importance of pleasure when she says, “pleasure is the point. Feeling good is not frivolous, it is freedom.”(Brown, 2019, p.174) Maree’s notion of pleasure as activism is central to queer interiors. She describes pleasure activism as “…the work we do to reclaim our whole, happy, and satisfiable selves from the impacts, delusions, and limitations of oppression and/or supremacy.”(Brown, 2019, p.7) Like queer space, the act of queer pleasure serves as a method to reclaim what was lost or suppressed. Queer pleasure within these spaces serves as a mode of resistance against heteronormativity and creates space for queer expression.

Pleasure and associated joy are not guaranteed in these spaces, and queer people can feel these emotions anywhere. We’re proposing this category to identify places where queer folks seek out a feeling of pleasure and joy not always possible in heteronormative environments. Stylistically these spaces of pleasure can vary significantly in design but share common attributes within their program. For example, seating is an important factor within these spaces. In each example, these interiors include both bar and table seating offering a range of social interaction. Bar seating allows for the intermixing of groups within the space while tables offer more intimate interactions to occur. Both options are necessary for fostering a space that creates a sense of comfort and connection. Aesthetically, bars typically employ dim lighting to create spaces that contain some mystery and curiosity, contrasted with dynamic lighting for performance and dance areas. Decorations, art, and brand elements in various styles from overtly sexual to “camp” can reinforce the pleasure-seeking mood.

Brown, A. M. (2019). Pleasure Activism: The Politics of Feeling Good. AK Press.

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Joy. In Meriam-Webster.com dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/joy

Queer Interiors of Care

The problems that face the queer community are diverse and unique. As a result, spaces of care are necessary for fostering a healthy sense of community. Regularly facing violence or discrimination in cis-heteronormative spaces, queer individuals rely on queer interiors of care to find support that would otherwise not be available. Although some examples of these spaces are more directly related to bodily health, mental health, and wellbeing, aspects of care often occur in community venues. Conversations and interactions allow for guidance to be passed within the community that assists in creating networks of support that are fundamental to queer interiors of care.

Interiors of care are made possible through a mixture of private and public programming within a space. For example, the care required for queer individuals can be achieved in a group setting but sometimes need more individual confidentiality. As a result, the programing for these interiors combines a mixture of open conversation spaces and rooms that can be closed to create a sense of safety and discretion. Not unlike mainstream, cis-heteronormative environments of care, the interior aesthetics of these places prioritize cleanliness, health, and safety. Bright colors and lighting reinforce these qualities while providing an uplifting environment that contrasts with other queer spaces (see Spaces of Pleasure).