Neutrino Catcher

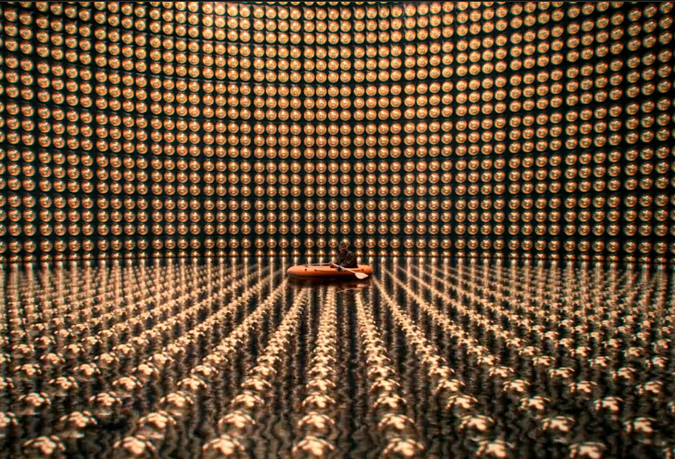

Super-Kamiokande Neutrino Catcher developed by the ICRR

Derived from the French word bouder, meaning to be sulky, the boudoir was as much a place for a woman to get dressed and socialize, as it was a prison for feminism. The eighteenth-century French boudoir used interior decoration to both reinforce notions of women as angelic, innocent, luxuriant, voluptuous, and cerebrally scattered and soft as well as provide women a modicum of freedom by allotting a personal space. In works of literature, such as Emile Zola’s mid-nineteenth-century novel The Kill, the boudoir is a place of intense sexuality, a characterization that acknowledges the typical dressing, undressing, and intimacy of the courtly boudoir. In her article ‘Furniture, Sociability, and the Work of Leisure in Eighteenth-Century France,’ Mimi Hellman asserts that the delicate interiors, especially the furniture and tools of the dressing room, emphasized physical aspects of a woman’s body, the twist of a wrist in opening a drawer calling attention to a woman’s delicate arms. She also notes that men characterized the space as a chamber where women would retreat to pout or tend to their womanly, frivolous thoughts. These were also rooms where married women conducted affairs with their lovers. The ideas and aesthetics introduced by eighteenth-century French boudoirs endure. The following collection of images briefly outlines both the stereotypically feminine aspects of eighteenth-century French boudoirs while tracing the influence of these rooms in the United States and Europe throughout the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first century.