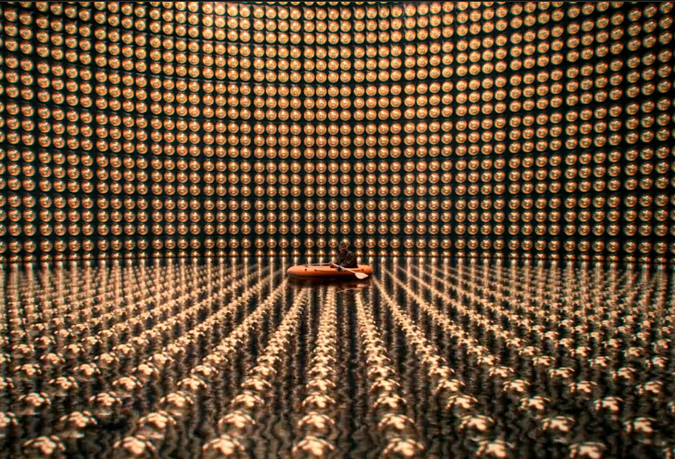

Neutrino Catcher

Super-Kamiokande Neutrino Catcher developed by the ICRR

Pat Kirkham and Sarah A. Lichtman’s Screen Interiors: From Country Houses to Cosmic Heterotopias (2021) pays homage to the vast world of set design immortalized on film over the past century. This interdisciplinary publication examines productions from a number of genres, demonstrating the power through which design can contribute not only to the aesthetic appeal of the film, but also serve as a medium through which the characters and plot can be conveyed. Rather than default to chronology the authors instead opt to approach the subject thematically. They identify six tropes which are inherently overlapping, and many of the films considered can fit comfortably into several different parts of the overall work. This structure invites readers to examine the films from different perspectives, thus gaining a greater sense of appreciation for the role that interiors can play in wider communication.

This anthology is the cumulative result of an interdisciplinary approach and serves as a testament to the growing academic interest in the study of interiors. One of the many strengths of the publication itself was the opportunity for scholars from a plurality of fields and geographies to contribute their research, thoughts, and experiences to each of the chapters.

The following is a curated selection of interiors from this book; a demonstration of just

one of many ways that the information contained within can be interpreted and utilized for the

purposes of comparison and contrast – a natural extension of the initiative that fueled the

foundation of the research itself.

House and Home: Comfort, Class, Gender, and Generation

“Drafted,” Season 1, Episode 11, aired December 24, 1951 (Source | Accessed : March 5, 2023)

Pilot for I Love Lucy, filmed March 2, 1951; aired April 30, 1990 on CBS. (Source | Accessed : March 5, 2023)

I Love Lucy, the 1950s American sitcom that remains amongst the most watched shows in the history of television, provides a quintessential example of design used as an opportunity to inform the audience about the lives of the beloved characters. Over the course of the series, the couple occupies three different apartments: Apartment 3B, Apartment 4A, and – by season 6 – a country home in Connecticut. Each of these settings, as well as the differences between them, are indicative of the changing societal dynamics that resonated throughout the post-war years throughout which the show was produced. Dr. Marilyn Cohen, faculty member at Parsons School of Design, interprets these changes within the context of four principles: comfort, class, gender, and generation.

Comfort, Cohen argues, is a difficult concept to convey to a heterogeneous audience, though the common thread of what people find to be comfortable is most often what they find to be familiar. This presented a problem for the show’s producers: the concern that middle-class American viewers would not find Ricky, a Cuban American, to be a familiar and thus comforting character. As a result, the décor seen throughout the home is notably absent of any reference to Hispanic culture whatsoever, unless it is placed to serve as a prop for a comedic punchline.

Despite the fact that I Love Lucy was filmed within the confines of a Hollywood studio complete with a live studio audience, the design of the set needed to convey the commonalities of domestic life in an authentic way. This was important if the television viewers were to view Lucy and Ricky as a real middle-class couple in their own home, as opposed to the wealthy Hollywood stars Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz were. The challenge of doing so, however, was the dramatic changes to what home life looked like in post-war America, where middle-class families enjoyed an unprecedented degree of purchasing power which enabled them to purchase a diversity of products. As Dr. Cohen identifies numerous objects found throughout the Ricardo’s home could be purchased in Sears, Roebuck catalogs – a ubiquitous source for furnishings found in middle class households throughout the country. This is notably exemplified when a piano first appears in the Ricardo’s home – a luxury that would’ve previously been associated with upper class residences had become a commonplace marker of “middle-class respectability” and “the family’s appreciation of music” that was conveniently able to be purchased in a mail order catalog without leaving the home.

The intentionality of these aesthetic decisions is especially pronounced when contrasting the Ricardos’ home throughout the series to the apartment that the show’s pilot episode was shot in. In this initial iteration, the décor was decidedly cosmopolitan, replete with references to modernist and mid-century modern design, which was all but foreign to the suburban middle-class families across the country. Conversely, the apartment that the couple would call home in subsequent episodes was more modestly decorated with Chippendale style furniture that resonated more effectively with the target audience, most of whom would not have been familiar with such well-known modern designers such as Charles and Ray Eames, let alone afford a set of their chairs.

The apartments of Lucy and Ricky Ricardo are far from the glamor of Manhattan, and instead intend to convey the couple as relatable members of the middle class. For a society still wrestling with Ricky’s character (as well as the actor himself) being of Cuban heritage, this relatability of his life in relation to the viewer required all the more attention to detail.

Gender plays an important part of I Love Lucy, and many of the 180 episodes reference, if not directly center around, the idea of gender roles. From the beginning of the series, it is well understood that Lucy aspired to be a performer but was instead condemned to a life as a housewife – a sentiment which she expresses through witty punchlines at numerous points throughout the series. These traditional gender roles are underscored throughout the initial designs of the Ricardo home – eliciting a feminine tone throughout the bedroom via the “quilted headboard, shiny, satiny fabrics, skirted vanity/dressing table, and ruffled curtains.” These aesthetic details also carried through into the kitchen, eliciting the idea that a woman was the primary utilizer of the space from “ceramic plates with floral or leaf patterns to stenciled decorations and [once again] ruffled curtains.”

The Curated Home

‘Funny Face’ directed by Stanley Donen © Paramount Pictures, 1957. All Rights Reserved. (Source | Accessed : March 10, 2023)

‘Funny Face’ directed by Stanley Donen © Paramount Pictures, 1957. All Rights Reserved. (Source | Accessed : March 10, 2023)

One of the aforementioned strengths of Screen Interiors is the degree to which interdisciplinary collaboration is utilized throughout the book. This is particularly evident in Rebecca C. Tuite’s analysis of fashion professionals at home in post-war filmography. By trade, Tuite is a fashion historian who recently published a retrospective on Vogue Magazine while

under the direction of the late editor Jessica Daves from 1952-1962. Here, she applies that expertise to the domestic interiors of the same people depicted in film from 1957-1961. Most notable amongst these films is Funny Face, a romantic comedy that further immortalized Audrey Hepburn as an eternal icon of both fashion and film alike. It is of note that Funny Face, which

was released in 1957 – the same year that I Love Lucy aired its final episode – depicts “career women” as opposed to the domestic gender roles that I Love Lucy had largely adhered to throughout the decade thus far. But, as with I Love Lucy, films of this era also reflected the newfound spending power of the middle class – enabling consumers to spend more on fashion and interior design than ever before. This spending was influenced by Funny Face and others like since as early as the 1920s, when overtly glamourous films that explicitly targeted the fantasies of women began being produced.

Framing Interiors and Interiorities

In the apartment’s kitchen Baxter demonstrates his culinary talent, draining the spaghetti onto a tennis racquet before serving it with meatballs. Fran is on the threshold of the kitchen. ‘The Apartment’ directed by Billy Wilder © 1960 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc. All rights reserved. (Source | Accessed : March 9, 2023)

Unlike Funny Face, 1960 romantic comedy-drama The Apartment uses interiors to illustrate a different type of desire. Two opposing interiors are notable here, the first being the protagonist’s bachelor apartment on West 69th Street and the second being his workplace, Consolidated Life Insurance’s corporate offices. Here the set works almost as a bland foil that serves to make the sinful lust of infidelity even more pronounced. While Funny Face is saturated with imagery of a romantic Parisian aesthetic, the protagonist of The Apartment is famously seen cooking spaghetti and meatballs in his small New York City kitchen utilizing a tennis racquet as a strainer. This is even further emphasized in the workplace, where the design of the office invokes the monotony through seemingly endless rows of identical desks arranged into rows that disappear into the background.

Horror and Homicide

mother/Lawrence works closely with the surfaces of the house wall, breathing life into the old house. (Source | Accessed : March 12, 2023)

One victim of the unnamed woman/Johansson as he sinks into the liquid surface of the cottage floor. (Source | Accessed : March 12, 2023)

In prior chapters, most notably House and Home: Comfort, Care, Gender, and Generation, the domestic interior is utilized to convey a sense of familiarity and stability – both literally and figuratively serving as the stable foundations upon which less stable characters acting within their confines interact. In contrast, Horror and Homicide exemplifies the antithesis of this approach – and is, in fact, successful in achieving its cinematic intention because of one’s assumption of the home being a locum of permanence and stability. This idea is epitomized in two films highlighted throughout this section: Under the Skin (2013) and mother! (2017). In both works, the houses within which the plots are set serve as dynamic, even living, entities that the protagonists not only interact with but are at times, even acted upon. As identified at several points throughout the chapters, this is a particularly effective technique in the creation of horror films because it disrupts our assumptions of the domestic interior as a benign establishment. In other words, it demonstrates that “things are not as they ought to be.” Thus, this subversion of people, things, and places that are generally regarded as safe and comfortable generates horror when successfully employed. Such approaches have allowed for an expansion of a genre that is otherwise often reduced to slasher films.

Similarly, Horror and Homicide also contrasts previous chapters by utilizing the interior as a means of also disrupting, rather than stabilizing, gender roles. In both films discussed, the protagonist is played by a woman who is acting against the patriarchal world that she exists in. Both the woman herself and the home within which she lives are not safe retreats for the male characters, but rather serve as unexpected threats to them.

Living in Outer Space: Sci-Fi Interiors

The Grand Concourse, Passengers, directed by Mortem Tyldum. © Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc., LSC Film Corporation, Village Roadshow Films Global Inc. and Wanda Culture Holding Co. Limited 2016. All rights reserved. (Source | Accessed : March 12, 2023)

The Vienna Suite, Passengers, directed by Mortem Tyldum. © Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc., LSC Film Corporation, Village Roadshow Films Global Inc. and Wanda Culture Holding Co. Limited 2016. All rights reserved. (Source | Accessed : March 12, 2023)

As in prior sections of the publication, Living in Outer Space also addresses concepts of comfort in relation to danger. This is most palpable in the discussion of Mortem Tyldum’s 2016 Science Fiction film Passengers (2016), which is almost entirely set within the confines of an intergalactic vessel named Avalon (1994), whose purpose is to transport its 5,258 hibernating inhabitants on a 120-year journey to a new colony formed on a nearby planet. The interior of the ship – which is explored by the protagonist (played by Chris Pratt) after unexpectedly awaking from his hibernation secondary to a technological malfunction – reflect not the super-futuristic, technologically-saturated rooms seen on the many prior depictions of spaceships on film, but rather one that is more akin to a modern day cruise ship, complete with restaurants, bars, and a shopping mall. The intention of this aesthetic decision, as discussed in the chapter, is to evoke emotions of comfort and familiarity that forms a striking contrast against the harsh, foreign darkness that lies beyond the vessel’s walls. Not unlike the interiors discussed in House and Home, the effect of this portrayal is the feeling of safety and comfort – commonalities that the ship’s passengers and the movie’s viewers alike can relate to.

As the film progresses, this benign-appearing interior is again employed through its subversion when the ship continues to malfunction, requiring the protagonist to enter the depths of Avalon’s underbelly, revealing a layers of advanced technology more akin to spaceship portrayals seen throughout the history of the genre. In doing so, the interior that was once a foundation of security is quickly realized for what it truly is: an aesthetic shell concealing the unfamiliar – a development that, as identified in Horrors and Homicide, can be utilized as a source for generating feelings of fear and uncertainty. In that section, both Under the Skin (2013) and mother! (2017) tempt both the characters and audience to trust in the security of the familiar: the domestic home, before it is quickly subverted into a foreign, malignant entity – generating the feeling that, “things are not as they ought to be.”

Hand-in-hand with the relationship between the sublime and banal is that of the past, present, and future – which are addressed in a fashion that is almost completely exclusive to the genre of Science Fiction. The challenge of such films is to create an aesthetic environment that is capable of anchoring the viewer to the plot’s relationship to the present day. In Passengers (2016) this is done by utilizing familiar interiors such as the shopping mall, as well as via the decision to furnish the Vienna Suite with 20th century designs such as a Warren Platner Coffee Table or Marc Newson’s Wood Chair. The effect is twofold: first, it orients the viewer to the relationship with their current reality given the familiarity of these iconic pieces, most strikingly for the generation of Baby Boomers for whom these designs came to fruition during their youth. The second is that it makes an unspoken statement with regards to the class of the tenants occupying the suite: standard hotel or cruise ship rooms are not furnished so lavishly, and even the modern reproductions of these works by Knoll lay financially out of reach for most consumers.

The equivalent, though opposite, effect is achieved in Firefly (2001), an early 21st century television series, later adapted into a feature film, which depicts the crew of the Serenity spaceship during their intergalactic travels. Unlike the interiors of the Avalon, the Serenity’s domestic living space is mismatched and cluttered – cluing the viewers into the fact that these protagonists do not exist within the socioeconomic class that a resident of the Avalon’s Vienna Suite does. Even before the plot’s progression reveals the motley crew to be surviving tenuously off of petty theft and a sparse income, one can insinuate their membership in the working class-equivalent of the post-Earth environment that Firefly is based in.

Conclusion

The study of interiors depicted on screen, taken in relation to the wider studies of Design History and Interior Design, remains a largely unexplored endeavor. Yet, as illustrated extensively throughout Screen Interiors: From Country Houses to Cosmic Heterotopias, it can serve as informative insight into wider perceptions of aesthetic choices based upon the Set Designer’s decision to build an environment that evokes sublimity versus banality, wealth versus poverty, familiarity versus the bizarre. Just as research into the furnishings of a grand estate provides potent insight into the lives, values, and interests of the aristocrats who occupied it, screen interiors can serve as equally sagacious material from which perceptions of the audience viewing it can be inferred. Yet, unlike the traditional study of interiors, those on screen are no longer limited by the constraints of time, money, geography, gravity, or even reality. What’s left is creativity in its purest form, where every aesthetic decision, no matter how minute, has the opportunity to meaningfully contribute to the story.

In the future, one can only predict the study of screen interiors to become a more predominant practice as advances in film technology continue to readily allow for the creation of environments that previously would have existed beyond the furthest frontier of the imagination of even the greatest filmmakers of past generations. Thus, aesthetic decisions that orient or disorient the viewer to the story’s relationship to their own reality will only grow in importance.