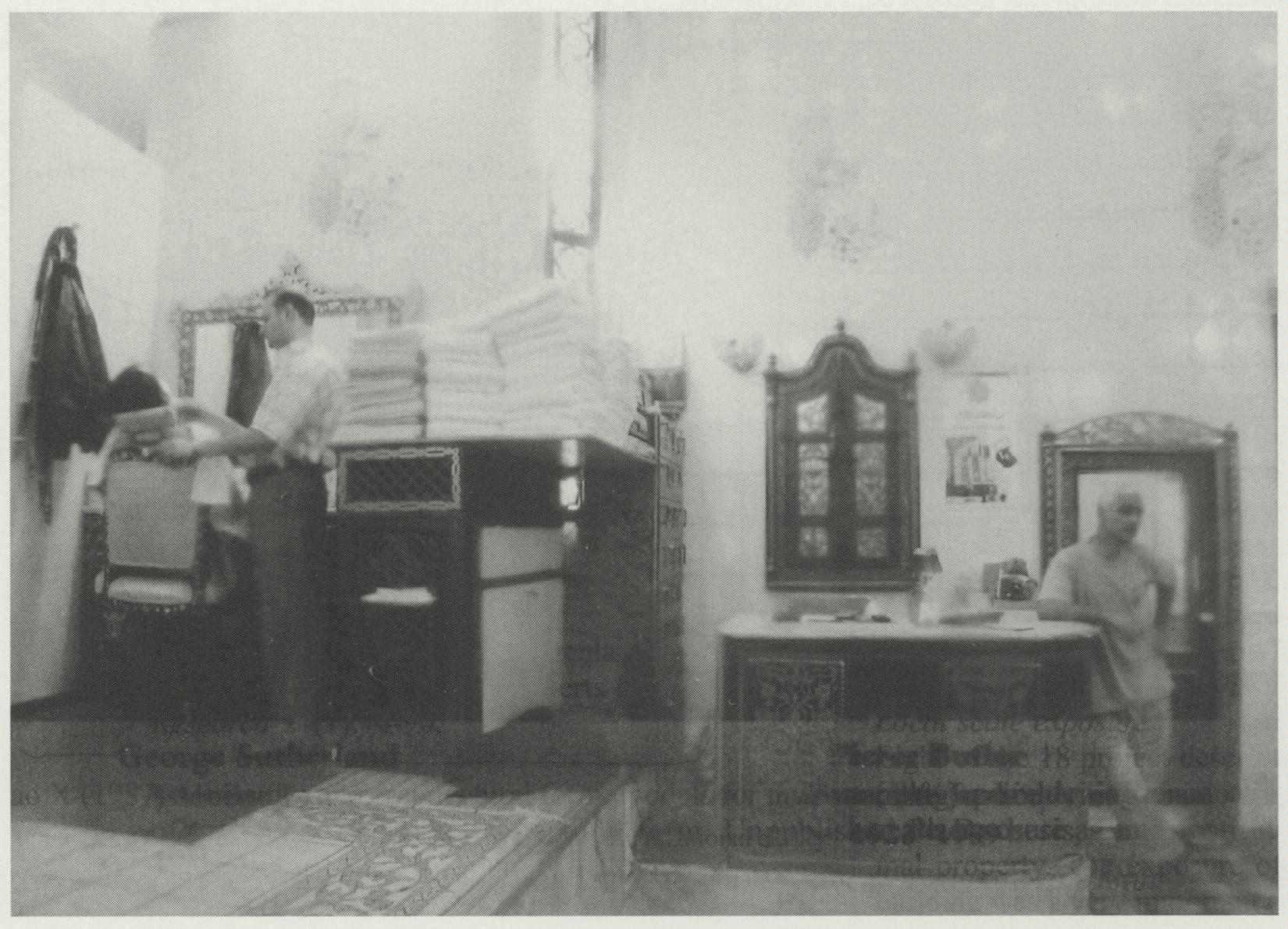

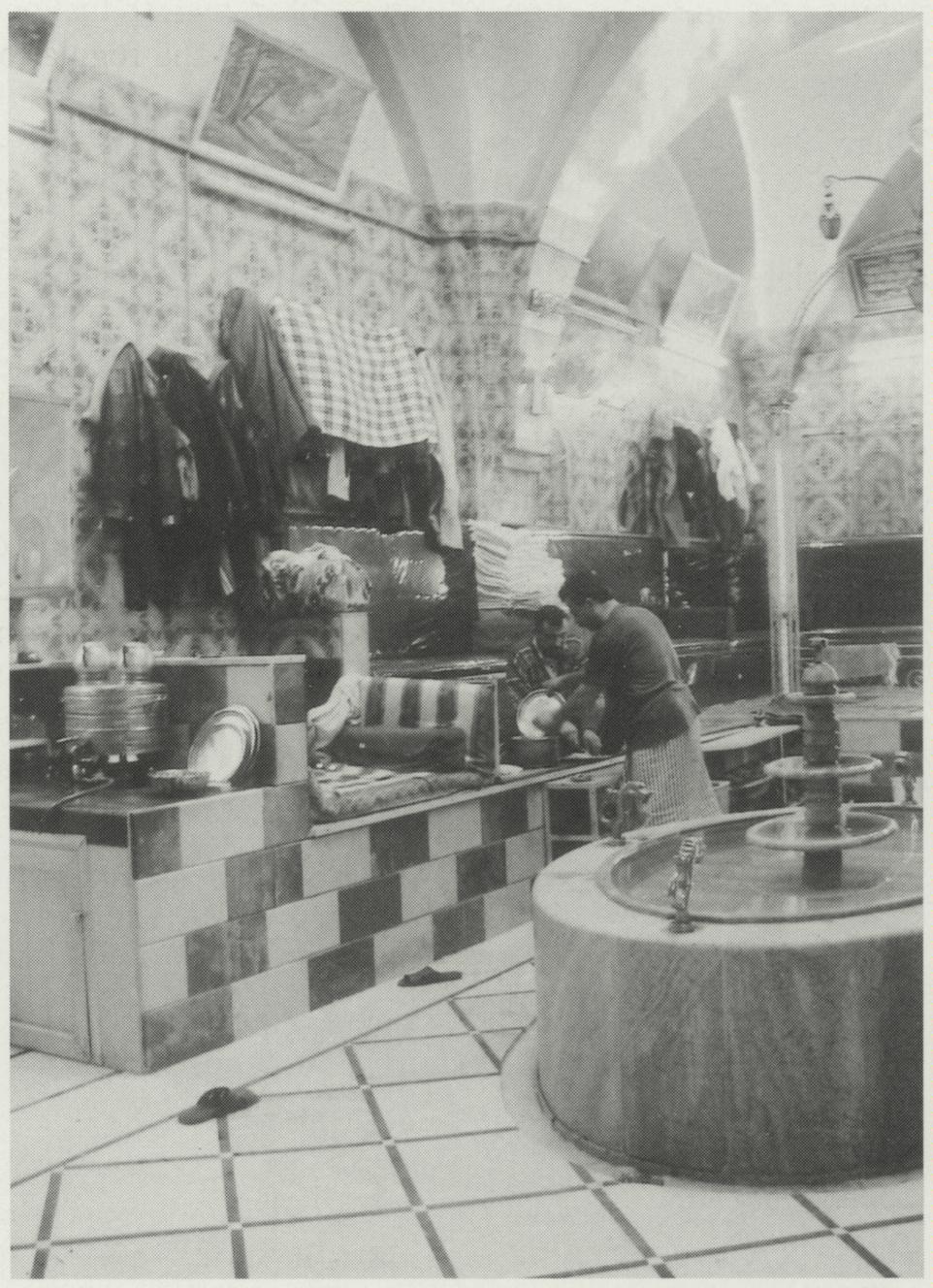

Hammâms, Damascus, Syria (12th-18th Century)*

Artist/Designer: North African, Islamic

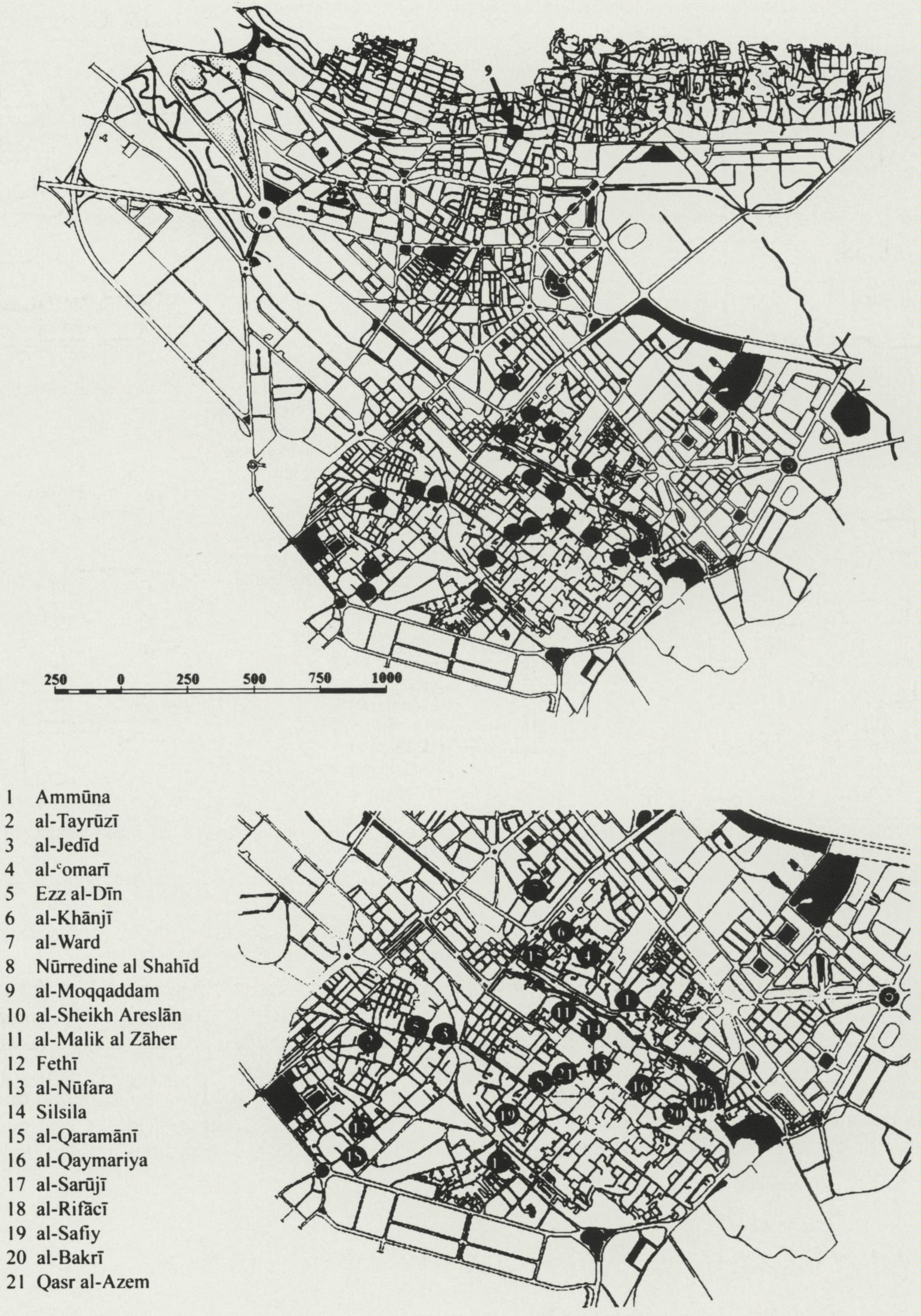

Project Location: Damascus, Syria

Style/Period(s):

Vernacular

Primary Material(s):

Ceramic, Stone

Function(s):

Health Facility

Related Website(s):

Significant Date(s):

12th Century, 13th Century, 14th Century, 15th Century, 16th Century, 17th Century, 18th Century

Additional Information:

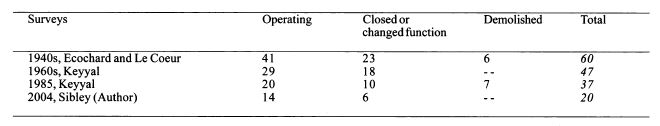

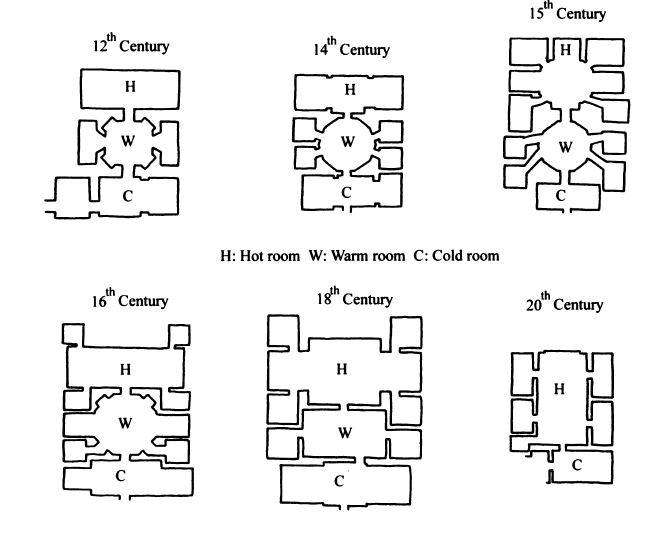

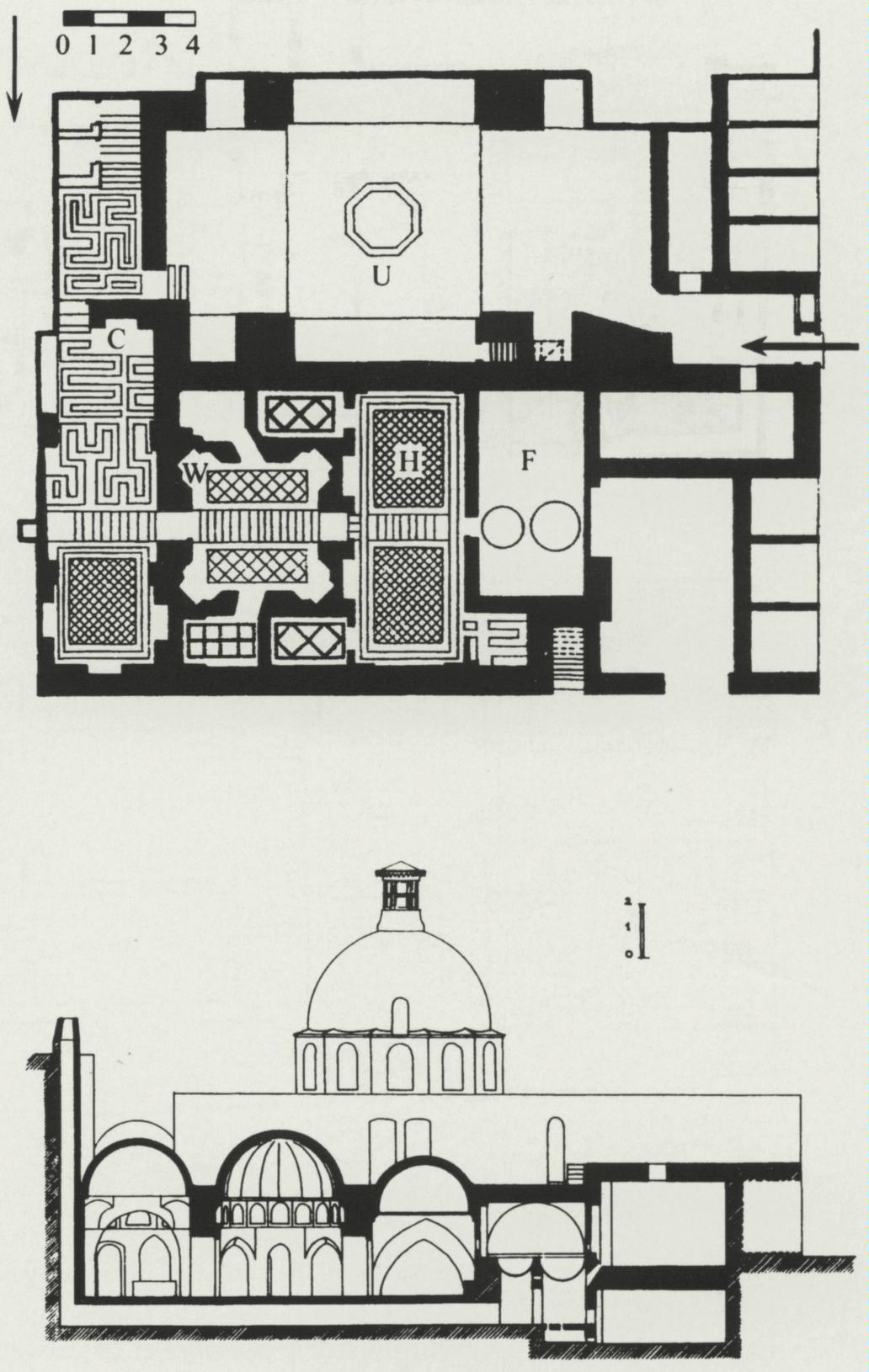

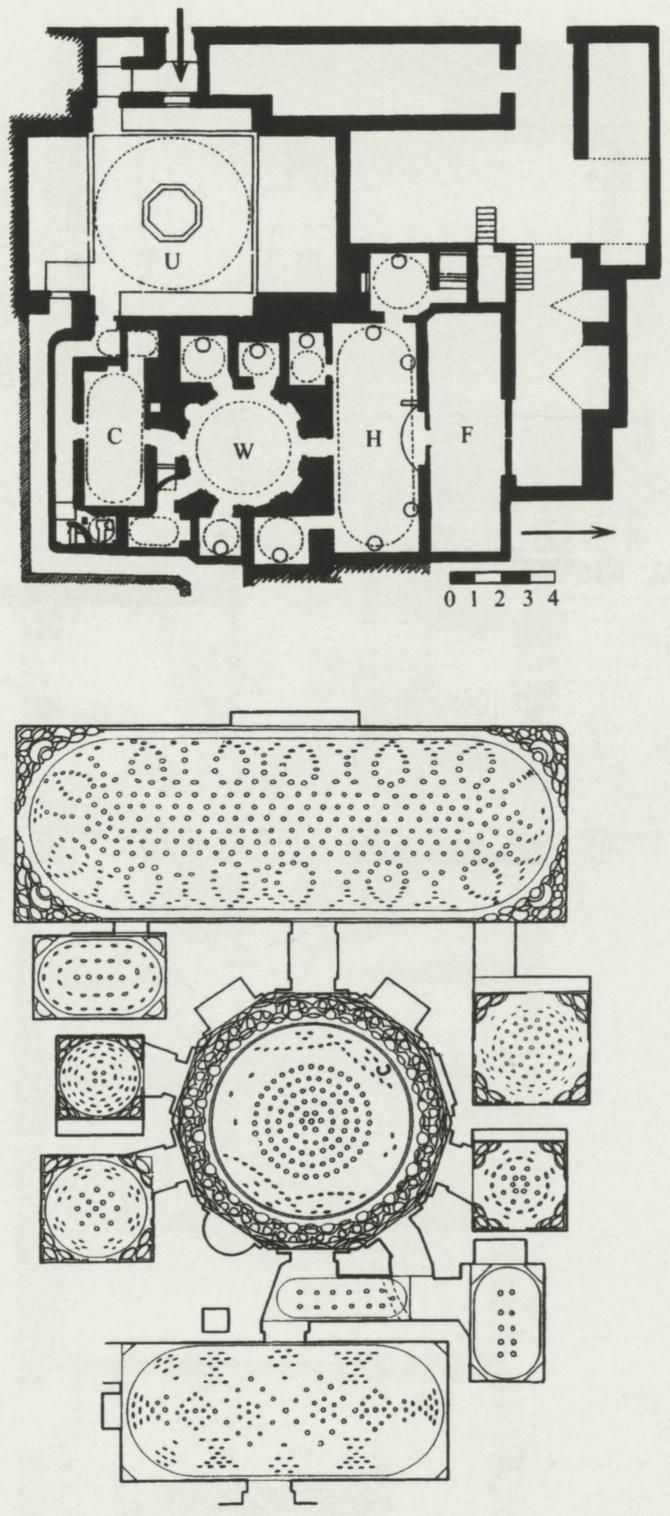

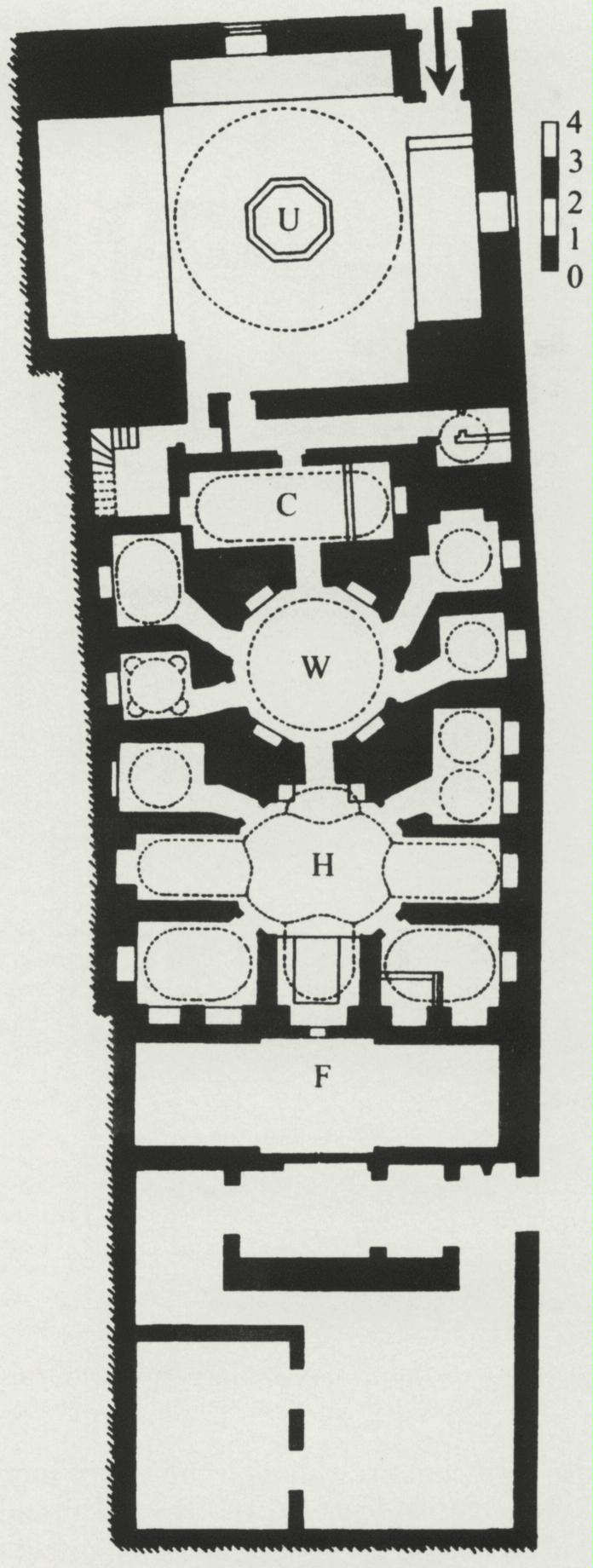

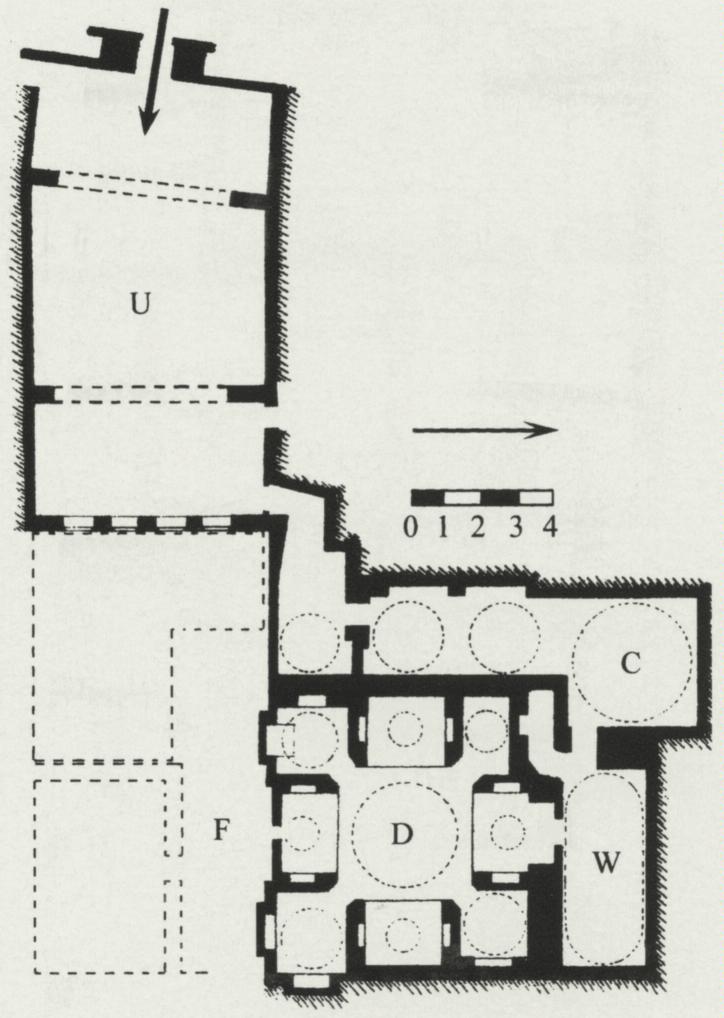

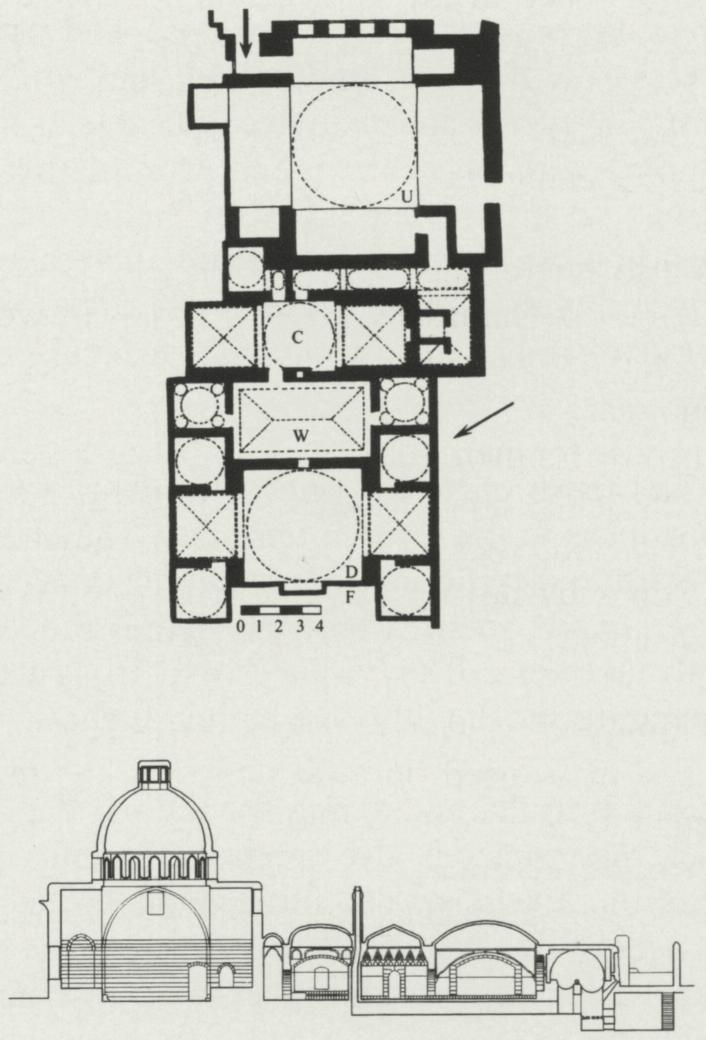

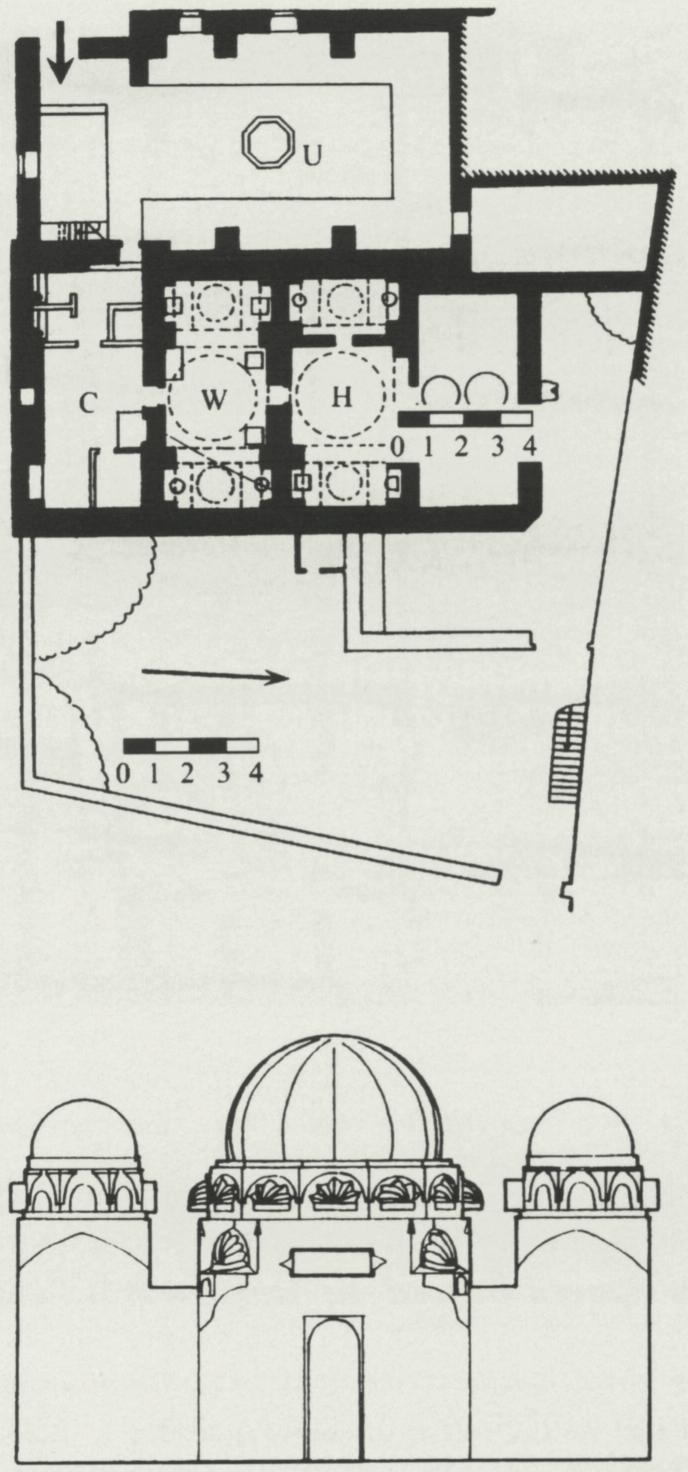

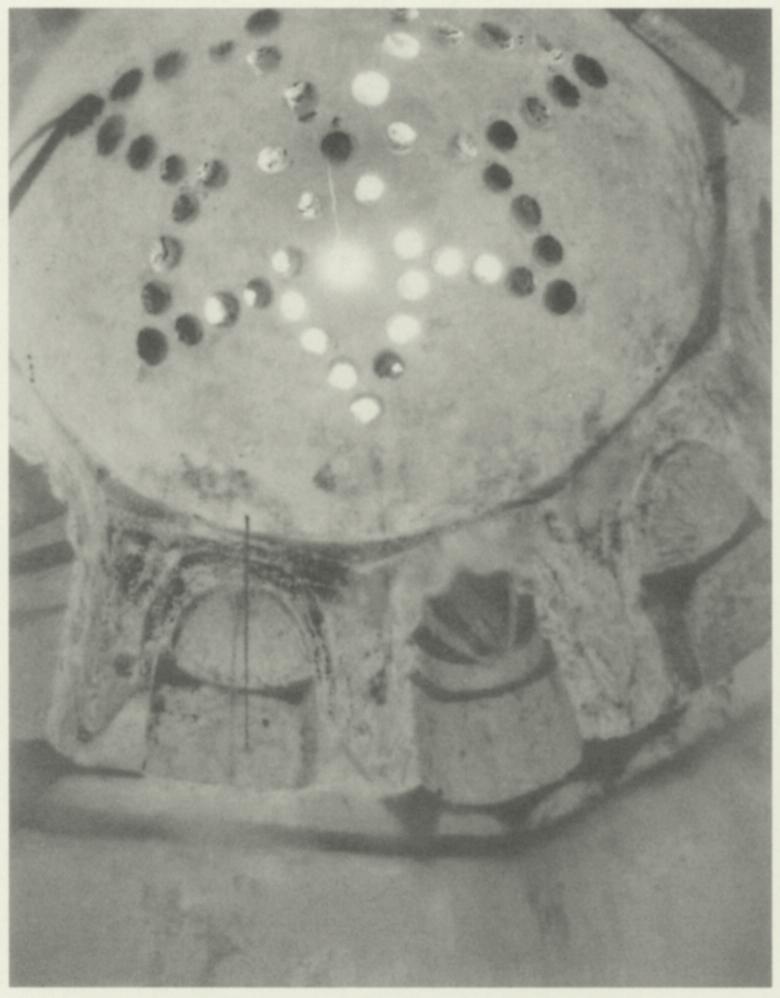

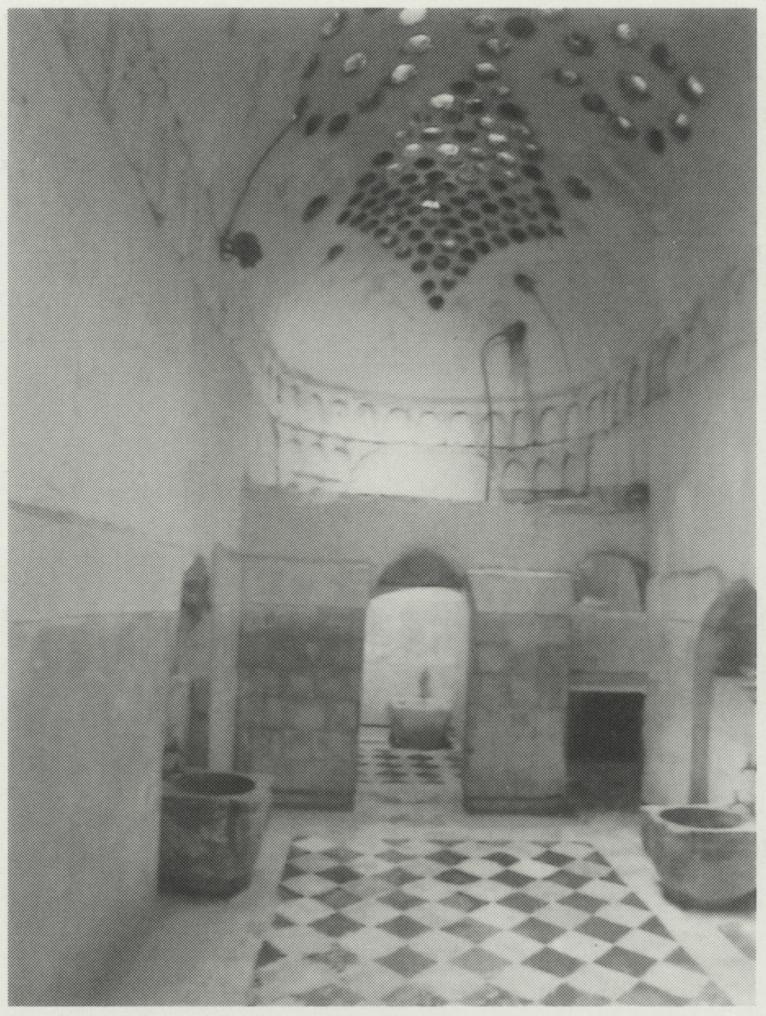

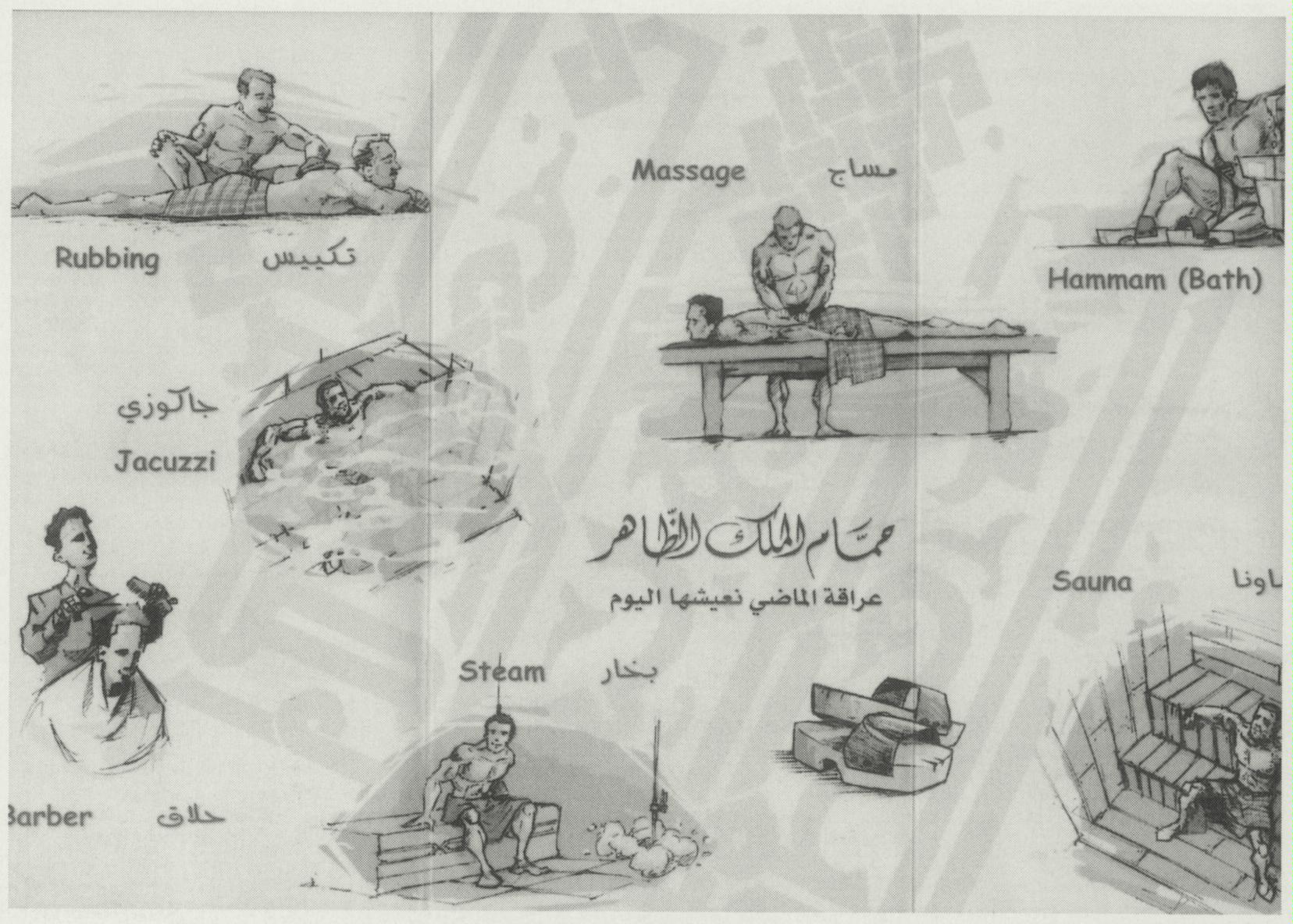

The early Islamic hammâms evolved by assimilating an existing institution into a new society. In the first century of the Islamic calendar (A.D. 622), there was a widespread number of Roman three-room compositions (frigidarium, tepidarium, and caldarium), and the first Islamic hammâms consisted of a linear progression of rooms with varying temperatures. The religious requirements in Islam played an important role in the way hammâms developed. For example, the cold major feature of the Roman baths disappeared in the Islamic baths. Although pools existed in some hammâms of Palestine and Greater Syria, bathing by immersion was not common during the period. Instead, bathing in running water became the norm. This was because bathing by immersion was considered inappropriate as tanks of less than 1,000 liters could not be used for ritual washing-water could be polluted by an unclean person. Hot pool bathing also became optional, carried out by pouring water over the bather. It is only in Egypt that plunge pools have an important part of every hammâm, possibly because of the availability of water from the Nile.

Publications/Books in Print:

Allsop, Robert Owen (1890), The Turkish bath: its design and construction, Spon

Blake, Stephen P. (2011). "Hamams in Mughal India and Safavid Iran: Climate and Culture in Two Early Modern Islamic Empires". In Ergin, Nina (ed.). Bathing Culture of Anatolian Civilizations: Architecture, History, and Imagination. Peeters. pp. 257–266.

Cosgrove, J. J. (2001) [1913], Design of the Turkish bath, Books for Business.

Fournier, Caroline (2016). Les Bains d'al-Andalus: VIIIe-XVe siècle. Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes.

Gazali, Münif Fehim (2001), Book of Shehzade, Dönence.

Staats, Valerie (1994). "Ritual, Strategy, or Convention: Social Meanings in the Traditional Women's Baths in Morocco". Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. 14: 1–18.

Shifrin, Malcolm (2015), Victorian Turkish baths, Swindon: Historic England

Sibley, Magda and Iain Jackson. "The Architecture of Islamic Public Baths of North Africa and the Middle East: An Analysis of their Internal Spatial Configurations." Arq : Architectural Research Quarterly 16, no. 2 (06, 2012): 155-170. doi:http://dx.doi.org.libproxy.newschool.edu/10.1017/S1359135512000462. https://login.libproxy.newschool.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.libproxy.newschool.edu/docview/1212338359?accountid=12261.

Sibley, Magda. "THE PRE-OTTOMAN PUBLIC BATHS OF DAMASCUS AND THEIR SURVIVAL INTO THE 21 ST CENTURY: AN ANALYTICAL SURVEY." Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 24, no. 4 (2007): 271-88.

Toledano, Ehud R. (2003), State and Society in Mid-Nineteenth-Century Egypt, Cambridge University Press.

Yilmazkaya, Orhan; Deniz, Ogurlu (2005), A light onto a tradition and culture: Turkish baths: a guide to the historic Turkish baths of Istanbul (2 ed.), Çitlembik.

Building Address: Multiple examples across North Africa. Examples are shown from Tunisia, Syria, Damascus

Tags: Middle East, Islamic, North Africa, Hammams, Roman, Health Facility, Public Baths, Bathing, Syria, Damascus, Tunesia, Archeological sites, Bath culture, Bathing culture, Bathing, aqueous, hygiene, hygienic, health, 18th century, 12th century, 13th century, 14th century, 15th century, 16th century, 17th century, ceramic, stone, hammâm, North Africa

Viewers should treat all images as copyrighted and refer to each image's links for copyright information.